FOOD AS MEDICINE: ANCIENT WISDOM VS. MODERN EVIDENCE

- Caleb Asharley

- Dec 17, 2025

- 14 min read

Introduction

The phrase “food as medicine” captures the idea that what we eat can do more than satisfy hunger; it reflects an ancient truth that what we eat profoundly influences how we live, heal, and age. Across civilisations, food was never seen as mere fuel but as a central part of maintaining balance, preventing illness, and supporting recovery. This concept is far from new; ancient traditions across the world, from Ayurveda in India to Hippocratic medicine in Greece, treated food as a central tool for healing. They viewed the body as an integrated system where health depended on harmony between diet, environment, and lifestyle. Food was the first line of defence, prescribed to restore equilibrium before disease took hold (Yao et al, 2023).

What’s exciting is that modern nutrition science is now revisiting these age-old ideas with rigorous research. Modern science continually validates this holistic worldview. Nutritional research now shows that food interacts with our biology on multiple levels, through metabolism, inflammation, immunity, and even gene expression. Diets rich in whole foods, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and healthy fats reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain types of cancer, reinforcing the preventive power of a balanced diet. Studies on inflammation, gut microbiota, and the prevention of chronic diseases are providing scientific validation to practices once considered purely traditional.

Another key idea is the continuum of care. Food supports not only prevention but also treatment and recovery. Hospitals and clinics now use medically tailored meals and produce-prescription programs to improve outcomes and lower healthcare costs, turning food into a validated component of modern medical care (Boggild, 2024, Frontiers in Nutrition).

Still, scientists urge a balance: food complements, but does not replace medicine. Evidence-based nutrition emphasises moderation, diversity, and long-term habits, not quick fixes or miracle foods

Food is medicine was a key initiative in the 2022 National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, and various States have launched coalitions to sustainably fund these programs. The Rockefeller Foundation, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute have announced more than $350 million in food is medicine research funding. Expert commentaries on the promise of food as medicine for preventing and treating chronic diseases have been published in leading scientific journals, and major research institutions have established initiatives focused on the concept of "food as medicine."

It is well established that offering food at no cost to those who need it is valuable. But the medical and public health communities’ enthusiasm for food as medicine appears unjustified by its likely benefit (JAMA, 2023).

However, not all experts agree on the scope of its promise. Commentaries in leading medical journals caution that enthusiasm sometimes exceeds the current strength of evidence. While providing healthy food to those in need has clear social value, researchers warn that Food-as-Medicine should complement, not replace, conventional medical treatment. Food as medicine encourages a shift entirely from treating disease to cultivating wellness.

Ancient Wisdom

Long before laboratories and clinical trials, civilizations across the world recognized that food could heal, energize, and restore balance. Every culture developed its own food philosophy, rooted in close observation of nature, the body, and the effects of diet on health and vitality. From Africa to Asia, the Mediterranean to the Americas, ancient civilizations saw food as both sustenance and a natural pharmacy guided by observation of nature, the body, and the effects of diet on health and vitality.

Many African societies relied on a varied, plant-rich diet drawn from native grains, leafy vegetables, fruits, and fermented staples. Such diets, built around foods like millet, sorghum, leafy greens, and native fruits and nuts, provided essential nutrients well adapted to local environments. A recent review highlights those traditional African diets, with their focus on whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and fermented foods, confer significant nutritional value and health benefits (Onian'go et al 2025).

Food In Early Societies

Africa: Food, Healing, and Vitality

Across ancient and precolonial Africa, food and medicine were inseparable. Communities used locally available plants not only for nourishment but also for healing. The baobab tree, often called the “tree of life,” provided vitamin C-rich fruit to strengthen immunity, leaves to treat fevers and inflammation, and bark for digestive ailments. Moringa leaves were consumed to boost energy, support lactation, and treat malnutrition. Fermented porridges made from sorghum or millet have been shown to improve gut health and digestion, while rooibos tea in South Africa is prized for its calming and detoxifying effects. In Ancient Egypt, workers who built the pyramids were given garlic and onions to increase stamina and resistance to infection. Honey was so valued for its antibacterial and wound-healing properties that it was used both as food and as medicine, and even placed in tombs for the afterlife. Egyptian medical papyri describe honey as a treatment for wounds, burns, and throat infections, centuries before its properties were scientifically understood.

Asia: The Art of Balance

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), foods were categorized as hot, cold, dry, or moist, each influencing the body’s internal equilibrium. Green tea was prescribed for detoxification, goji berries to nourish the eyes and liver, and ginger to relieve nausea and colds. Maintaining harmony between Yin and Yang through food was considered the foundation of health.

Similarly, in Ayurveda (India), diet was used to balance the body’s three doshas, Vata, Pitta, and Kapha. Spices like turmeric, cumin, and coriander were daily medicinal agents for digestion, inflammation, and longevity, practices that modern science now validates.

The Mediterranean & Near East: Diet as Daily Therapy

In ancient Greece and Rome, food played a central role in medical philosophy. Hippocrates, the “Father of Medicine,” taught that “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.” Olive oil, herbs, fermented dairy, and moderate wine were believed to nurture vitality and mental clarity. In the Near East, honey and dates were symbols of life and healing, while olive oil was used both as a source of nourishment and as an anointing medicine. Diet was viewed as a means of maintaining balance between the body and nature, a principle that still underlies the modern Mediterranean diet.

The Americas: Sacred Nourishment

Among Mesoamerican cultures, maize (corn) was sacred, the very substance of life. Cacao, taken as a bitter drink, was believed to boost energy and mood; chilli peppers supported digestion and circulation. Indigenous North Americans valued cranberries for urinary health, maple sap as a spring tonic, and willow bark (rich in salicylic acid, the precursor of aspirin) as a pain reliever. Food was intertwined with spirituality; what nourished the body also honored the earth and sustained the community.

Europe: The Humors and the Table

In Elizabethan England, the ancient Greek theory of the four humours, hot, cold, moist, and dry, still governed food choices. Meals were designed to restore the body’s internal balance. Bread, meats, and fish were assigned specific qualities, while herbs such as rosemary, sage, and mint were believed to strengthen memory and aid digestion. Even luxury items like spices and sugar were medicinal, thought to “warm” the body and ward off disease. Ale and beer were brewed with herbs, reflecting the belief that every drink had therapeutic meaning.

A Shared Legacy

Across all continents, ancient food practices shared a profound truth: the act of eating was both nourishment and medicine. Garlic and honey in Egypt, turmeric in India, olive oil in Greece, baobab in Africa, and cacao in Mesoamerica; each was used not just to feed but to heal. Modern science now confirms much of this ancestral knowledge: garlic’s allicin supports cardiovascular health, fermented foods nurture gut bacteria, and plant polyphenols reduce inflammation. Ancient wisdom endures, reminding us that health begins not in the pharmacy but in the kitchen.

Modern Evidence: How Science is Proving Food Really Can Be Medicine

Modern nutrition science is giving new credibility to something humans have always believed: that what we eat can help heal, prevent disease, and even shape how we age. However, instead of relying on ancient intuition, today’s understanding is based on data, biomarkers, and decades of research that connect diet to chronic disease and overall well-being.

Food Patterns, Not Just Superfoods

While ancient wisdom framed food as healing, today’s science provides measurable proof. Researchers are uncovering the biological mechanisms by which foods and their active compounds, called nutraceuticals, support health and prevent disease. Recent research shows it’s not about a single “miracle food,” but the overall pattern of what we eat. Diets rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains consistently lower risks of heart disease, diabetes, and obesity.

A 2023 review of global nutrition studies found that people who followed high-quality, whole-food diets had much lower cardiovascular mortality and inflammation than those eating typical Western diets (Taylor, 2023 PubMed). Another large analysis confirmed that Mediterranean-style eating improves blood pressure, body weight, and metabolic health, especially in people with existing heart conditions (Nutritional Journal, 2024).

These findings show that “food as medicine” isn’t just philosophy; it’s measurable biology.

Diet and Chronic Disease

The evidence is especially strong in metabolic health. Studies show that dietary interventions can reduce blood sugar, cholesterol, and weight, key risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

A 2025 systematic review found that patients with type 2 diabetes who followed structured dietary programs improved their glucose control and often needed fewer medications (Nutrition & Metabolism, 2025). Similarly, another meta-analysis revealed that plant-based diets reduced insulin resistance and improved lipid profiles in people at risk of heart disease (PubMed, 2025).

Put simply, eating the right foods can help manage, and sometimes even reverse the early stages of chronic disease.

Why Food Works: The Science Behind

Modern studies now explain what ancient healers could only observe.

· Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects: Nutrients in berries, olive oil, and leafy greens help calm inflammation, a key driver of heart disease, diabetes, and even depression.

· Metabolic regulation: Whole foods with low glycemic load, like lentils and oats, stabilize blood sugar and reduce insulin resistance.

· Gut microbiome health: Fermented foods like yogurt, cheese, miso etc, promote beneficial bacteria, improving digestion, mood, and immunity.

· Heart and liver protection: Healthy fats and plant fibers lower triglycerides and reduce fatty liver markers.

Balancing Hype with Evidence

While the science is compelling, experts stress that food isn’t a replacement for medicine; it is a partner. Studies show diet can reduce risk, improve biomarkers, and enhance treatment outcomes, but it rarely acts as a “cure.” Results also vary depending on culture, genetics, and consistency, meaning what works for one population might not for another.

The consensus is clear: every meal is an opportunity, not just for nourishment, but for healing. Food alone can’t fix every illness, but without the right food, healing becomes much harder.” – Gather such parts and use them as a conclusion.

Comparison

When we set ancient traditions alongside modern scientific research, a fascinating dialogue emerges. Ancient people did not know the language of antioxidants, omega-3s, or gut microbiota, yet through centuries of observation, they often identified foods that truly influenced health.

Take garlic and honey, for example. In Egypt, garlic was given to laborers for stamina, while honey was used to heal wounds. Today, garlic is recognized for its allicin content, which helps lower blood pressure and cholesterol, while honey is validated for its antibacterial and wound-healing properties. Similarly, olive oil, central to Mediterranean diets for millennia, is now backed by robust evidence showing its monounsaturated fats protect cardiovascular health.

Fermented foods provide another striking continuity. From miso and kimchi in Asia to fermented sorghum in Africa and yogurt in the Mediterranean, fermentation was originally about preservation but was also linked to vitality. Modern microbiome science now reveals why: these foods introduce beneficial bacteria that support digestion, immunity, and even mental well-being.

Mesoamerican traditions add yet another dimension. Cacao, consumed as a bitter drink for energy, is today understood to improve blood flow and brain function through flavanols. Chili peppers, valued for vigor and heat, are now studied for capsaicin, a compound linked to improved metabolism and even pain relief.

Fruits like pomegranates, figs, and dates, cherished in ancient Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cultures, are celebrated today for their antioxidants, fiber, and micronutrients that reduce risks of chronic disease.

At times, science confirms ancient practices almost entirely, as in the case of garlic or fermented foods. At other times, it refines the story, wine, once praised for vitality and digestion, is now understood to have potential benefits only in moderation, and with clear risks if overused. This comparison reveals that food can still be considered medicinal.

NUTRIGENOMICS AND PERSONALIZED NUTRITION

Nutrigenomics & Personalized Nutrition: When DNA Meets Diet

Our traditional dietary guidelines tend to be one-size-fits-all: eat a balanced plate, limit sugars and saturated fat and get enough fruits and veggies. But what if that advice could be fine-tuned to your genetic makeup? That’s the promise of nutrigenomics, a growing field exploring how genes and food interact, and how personalized nutrition might offer deeper health benefits than generic diets.

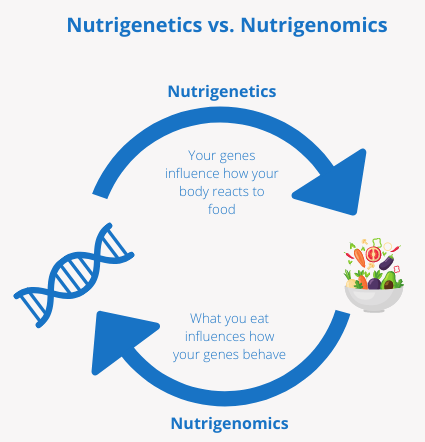

Nutrigenomics: The study of how nutrients and bioactive compounds in food influence the expression of our genes, turning certain genes “on” or “off,” affecting metabolic pathways, inflammation, detoxification, and more.

Nutrigenetics: Studies how our inherited genetic differences (such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)) affect our ability to metabolize nutrients, respond to fats or carbohydrates, or even absorb vitamins.

As promising as nutrigenomics sounds, experts caution against over-promising. There are a few factors to consider:

Many studies look only at single nutrients or single gene variants, but real people have complex genetics and dietary patterns, making it hard to draw firm conclusions.

The field is still emerging: long-term, large-scale clinical trials are limited.

There are practical and ethical challenges. Genetic testing is still not universally accessible or affordable, interpreting results correctly requires trained professionals and there are concerns about privacy, equity, and potential misuse.

For now, nutrigenomics is best seen as a complement to, not a replacement for, established healthy-eating principles.

THE GUT MICROBIOME: NEW FRONTIER

Modern science reveals that within us lives a complex, dynamic ecosystem, trillions of microbes (bacteria, yeasts, etc.) inhabiting our gut. This microbiome isn’t just background noise: it plays a central role in metabolism, immunity, digestion, and even mental health. What we eat directly shapes this ecosystem, making the gut microbiome a critical mediator of “food as medicine.”

What Is the Gut Microbiome and Why Does It Matter?

The gut microbiome refers to the collective community of microbes living in the digestive tract. Its combined genetic repertoire (“microbiome”) massively exceeds our human genome in metabolic potential, enabling digestion, nutrient extraction, and biochemical transformations that our bodies alone cannot perform.

A healthy, balanced microbiome supports digestion of complex carbohydrates, fibre, polyphenols and other compounds; produces beneficial metabolites; helps regulate immune responses; and protects against invasion by harmful pathogens (European Journal of Nutrition).

Disruptions in microbiome balance (so-called “dysbiosis”) have been associated with obesity, metabolic disorders, inflammatory diseases, gut problems, and impaired immunity.

Diet Shapes the Microbiome: What Research Shows

Many recent studies show that what we eat, especially overall dietary patterns, profoundly influences the composition and function of gut microbes.

Diets rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fibre, and plant-based foods promote a diverse and stable microbiome, supporting the production of beneficial meabolites (From Diet to Microbiota, 2025)

Consuming fermented foods and traditional fermented diets (yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, fermented grains, etc.) can introduce beneficial microbes or support existing beneficial bacteria, which may improve gut barrier integrity, immune function, and metabolic balance (Park and Mannaa, 2025)

By contrast, highly processed “Western-style” diets, heavy in processed foods, sugars, saturated fats, and low in fibre, have been shown to reduce microbial diversity, impair microbiome recovery (e.g., after antibiotic exposure) and increase risk factors for inflammation and disease (ScienceDaily, 2025).

How Microbes Mediate Food’s Health Effects

The microbiome affects our health in several ways, throwing light on how “food as medicine” actually works biologically:

Fermentation of fiber and complex carbs: Gut bacteria break down dietary fibers and resistant starches that human enzymes cannot digest, producing metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that feed colon cells, reduce inflammation, support metabolic health, and regulate immune function.

Metabolism of bioactive compounds: Many plant components (polyphenols, phytonutrients) require microbial action to become biologically available or active. The microbiome’s enzymes augment our own metabolic toolkit.

Immune regulation & inflammation control: A balanced microbiome helps maintain a healthy gut barrier, modulates immune responses, and minimizes chronic low-grade inflammation, a risk factor in many modern non-communicable diseases (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.).

Gut-brain and systemic effects: Emerging research shows microbiome activity influences not only digestion but also hormonal, neural, and metabolic pathways, potentially affecting mood, cognition, and systemic health beyond the gut.

Thus, the microbiome acts as a biological translator, converting what we eat into signals and substances that shape our health at multiple levels.

The microbiome isn’t a fringe, niche discovery; it’s central to nearly every way food affects our body. By shaping our internal microbial ecosystem, diet becomes not just fuel, but a modulator of metabolism, immunity, mood, chronic disease risk, and healing potential.

Incorporating microbiome-aware nutrition into global and personal health means revisiting traditional diets, valuing fiber and fermented foods, and embracing long-term dietary habits rather than quick fixes. In doing so, we bring ancient wisdom and modern science together, with the microbiome as the bridge.

Food as a Prescription in Modern Healthcare

The idea of prescribing food instead of or alongside traditional medications is rapidly gaining ground in modern healthcare. Known as Medically Tailored Meals (MTMs), these programs integrate nutrition directly into clinical treatment. Physicians and healthcare systems now provide patients, particularly those living with chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, with access to free or subsidized fruits, vegetables, and whole foods through clinics and community partnerships.

In the U.S., the Food is Medicine framework gained national recognition through the 2022 White House National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, marking a turning point in how health systems view nutrition. Major organizations, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH), The Rockefeller Foundation, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), have since committed over $350 million to study how medically tailored meals and produce prescriptions affect patient outcomes and healthcare costs.

Early results are promising. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), participants in food prescription programs experience 30–40% fewer hospital admissions, improved quality of life, and significant reductions in healthcare spending (CDC). Yet experts caution that enthusiasm must be matched by rigorous evidence and equitable access; healthy food must be available to everyone, not just prescribed in theory.

The Rise of Nutritional Misinformation

While the movement toward “food as medicine” is grounded in science, it has also sparked a wave of wellness fads, misinformation, and extreme dietary trends. Social media and influencer culture have blurred the line between evidence-based nutrition and pseudoscience. Detox diets, miracle supplements, and “anti-inflammatory” regimens often promise quick fixes without clinical proof. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), online nutrition misinformation has become a global public health issue, contributing to anxiety, malnutrition, and eating disorders.

The Problem with “Food as Cure-All”

When food is treated as a replacement for medicine rather than a partner, risks arise. For example, relying solely on restrictive diets for managing serious illnesses like cancer or diabetes can delay effective treatment. Various studies warn that overmedicalizing food can lead to confusion, guilt, and unrealistic expectations about the potency of diet.

Policy Implications

Policymakers are beginning to view traditional foodways as valuable public health assets. The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) and UNESCO both advocate for protecting traditional diets as part of sustainable nutrition strategies (FAO, 2024).By blending cultural food systems with scientific evidence, governments can promote diets that are both healthier and culturally meaningful.

Every Meal Matters

The story of food as a medicine stretches from ancient herbal studies to modern diet and genomic science, from cultural kitchens to national healthcare policy. Modern science is catching up with ancient wisdom.

Rigorous trials, meta-analyses, and public health data now confirm that food is one of the most powerful tools we have to prevent and manage chronic disease. From the molecular level to entire healthcare systems, food as medicine is no longer a metaphor; it’s becoming mainstream medical practice. What began as ancestral wisdom is now being validated through research, policy, and medical innovation. Yet its message remains timeless: food heals best when it nourishes both body and culture.

It is not about replacing drugs with diets, but about recognising diet as a powerful partner in prevention and therapy. Ancient wisdom offers inspiration; modern science offers validation and caution. Together, they remind us that every meal can be both nourishment and medicine.

REFERENCES

1. Bach Faig, A. et al. (2011) Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutrition, 14(12), pp.2274–2284. DOI: 10.1017/S1368980011002515.

2. Barber, T.M., Kabisch, S., Pfeiffer, A.F.H. & Weickert, M.O. (2023) The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Health and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients, 15(9):2150. DOI: 10.3390/nu15092150.

3. Berry, S.E. et al. (2020) Human post-prandial responses to food and gut microbiome effects. Nature Medicine, 26, pp.964–973.

4. Harvard Health (2025). Food Is Medicine: simple science-backed eating for better health and healing. Harvard Medical School. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/nutrition/food is medicine (accessed Dec 14, 2025).

5. Lean, M.E.J. et al. (2018) Diabetes remission with intensive weight management (DiRECT trial). Lancet, 391, pp.541–551.

6. Mediterranean diet, gut microbiota, and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention trials (2025). Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases. DOI: 10.1016/j.numecd.2025.104433.

7. Mukherjee, A., Breselge, S., Dimidi, E. et al. (2024). Fermented foods and gastrointestinal health: underlying mechanisms. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 21(4), pp.248–266. DOI: 10.1038/s41575 023 00869 x

8. Park, I. (2025). Fermented Foods as Functional Systems: Microbial Dynamics and Human Health. Foods, 14(13):2292. DOI: 10.3390/foods14132292.

9. Rahman, M.S. (2024). Integrating food is medicine and regenerative agriculture for human and planetary health. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11:1508530. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1508530.

10. Sanz, Y. et al. (2025). The gut microbiome connects nutrition and human health. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 22, pp.534–555. DOI: 10.1038/s41575 025 01133 0.

11. Volpp, K.G. et al. (2023). Food Is Medicine: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001182.

Comments